(this is the documentation for a previous A&S entry)

A Powder of Curry

In modern times, cooks tend

to take whatever shortcuts are necessary.

We go for spice blends that remind of us what we should be cooking --

whether it’s a pepper blend for Cajun cooking, a jerk chicken blend for

Caribbean fare, or curry powder for Indian food.

But what is considered Indian

food today is actually a conglomeration of cuisines, primarily that of the

southern part of the subcontinent and of English cookery, combined by wives and

servants brought by the English to southern India in the late 16th

and early 17th Centuries to appease the English palate with what was

available.

In her book Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, Lindsey

Collingham describes the process that the cuisine took, from its true roots on

the dirt kitchen floors of India to the barracks for soldiers to the English

housewife and the introduction of Indian spices into the world of fish and

chips. In the book, Collingham cites

many examples of what is considered to be Indian fare across the world, and

traces its origins to the creation of the curry powder.

Collingham contends that the

term “curry” is actually a European term (think The Forme of Curye)

-- a term that the was synonymous with “cuisine.” Though the term may be European, the spice

blend is certainly not.

Collingham and Indian Food

Historian K.T. Achaya agree on the British influence in the name, and that the

term “curry” may have well referred to any sort of Indian-esque dish. In fact, Achaya points out in his book Indian

Food: A Historical Companion that

the term “curry” is defined not as a spice blend in India but as a gravy served

with or over meat or vegetables.

In fact, the closest thing we

have to a western viewpoint on Indian cuisine would be that of French explorer

Francis Bernier, who traveled the Moghul empire in 1656, a half century outside

of our purvey of cuisine in SCA times.

Bernier did describe elaborate meals presented in the post-Akbarian

courts of the Moghuls, and expounded on the cooking methods therein used. Throughout his landmark tome, Travels in

the Moghul Empire, Bernier never

mentions any sort of powder in use in the courts.

Collingham’s work does trace

the eponymous beginnings of curry powder.

She notes the appearance in the late 18th Century of a “curry

powder” in English cookbooks, but none in Indian texts.

So does this make curry

powder a non-period item?

I found myself searching for

the answer to this question when I began my research for a feast back in

2004. I had been collecting redactions

and period mentions of dishes in Northern India for my documentation, but had

at the time been unsuccessful in locating any actual period recipes I could

work on redacting. To a fault, I found

that every recipe I had encountered at the time contained at least some

reference to “curry powder.”

The easiest part of my

research would come from finding out what’s in modern curry powder. That wasn’t as hard as I thought. Through the blessings of good timing, an

Indian grocery store had just opened up not far from my home. I simply purchased several types of curry

powder, went home, and read the labels.

What I found was a preponderance of ingredients that varied as much as

you might expect the spice blend to change between one cook and another at a

chili cookoff. Very few items were

standard.

I had at the time recently

discovered Achaya’s research. This

scientist and eminent researcher worked with India’s Council of Scientific and

Industrial Research and had in his efforts help define the very history of

Indian cuisine. I only regret that I had

not discovered his work earlier; he passed away in 2002. In the book Indian Food: A Historical Companion, Achaya told of

his visits to archaeological digs throughout India, and of his careful

documentation of the remnants of food at such sites. He talked with teams that had found cloves

burned to ancient floors and long and black peppers contained in partially

crushed clay vessels. Through this book

and through A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food, I was able to

document the spices used in the powders.

At the time, I was all about “faster

and better.” I knew that the feast ahead

would take much time and effort, and I aimed to take whatever shortcuts I could

to make sure patrons weren’t waiting for their supper for an undue length of

time. Through experimentation and by

utilizing only spices and herbs that were documented in Achaya’s work from

archaeological digs, I was able to create a spice blend of my own to use in my

cooking.

I could have quite easily

walked away after the feast and had nothing more to do with any of the

different cuisines I had so painstakingly researched for the project. But my curiosity was still there. Moreso, my husband was still there, and he

had developed a particular fondness for the curry blend I had created. So I continued to periodically gather the

ingredients and grind them for the blend that I used, and I started to share

this blend with others.

However, a kind lady with

Al-Mahala at Gulf Wars encouraged me to take a further step and teach about the

very spices I was using in my curry powders.

I felt that some explanation for each spice was necessary, and so I came

up with a course curriculum that featured all of the spices I had researched in

my efforts. I even offered a hands-on

class where participants could mix bits of dried spices to take home and try in

their own homes.

In my class handouts and in

the class itself, I shared the following information about the spices that

might be found in curry powders, and why I chose the spices I did for my own

blend. I also mentioned that the idea of

curry powder itself is a post-SCA time period invention, and encouraged my

students to seek out more information and whole spices so they could experiment

with their own attempts.

The spices I included in my

paper are as follows. The information

about each spice was culled from Achaya‘s archeological digs and from

references in Bernier‘s epistle and Collingham‘s later work, derived from

cookbooks of the British Raj era and later.

Further cited works are referenced with each relevant spice.

Bay Leaves: In

period, these would not have been the laurel leaves we know of today. Achaya found the similar shaped and sized tej

pat, a plant of the Indian subcontinent, in kitchen remains. The plant is known as Cinnamomum tejpata or

the more modern Malabathrum. Its leaf

has a flavor similar to cinnamon, but much milder. Unfortunately, confusion between the two has

resulted in the traditional European bay leaf being included in many modern

curry spice mixtures. Apicius cites the

use of bay laurel leaves many times in his Roman era cookbook De Re

Coquinaria.

Cardamom: There

are actually two very different sort of cardamom -- green and black. Green cardamom (Eletaria cardamomum) is

a green fibrous pod derived from a plant similar to the ginger plant. Its flavors range from eucalyptus to citrus

and it is considered far milder than its similarly named cousin. Black cardamom (Cardamomum amomum) is

a dark brown pod that brings smoky and camphor-like flavors to food. It’s often used in tandoori-cooked foods like

modern cooks use Liquid Smoke -- as a smoke-flavor agent. If you have tried Chai tea, you have likely

consumed green cardamom. Achaya noted

both of the cardamoms in kitchen ruins.

Both plants originate from southern India and Sri Lanka.

Cassia and Cinnamon: These two

barks are similar in nature, though cassia is generally less pungent and spicy

than cinnamon. Cassia is mentioned in

the Bible (Exodus 30:23-24) as ingredients to anoint the Ark of the

Covenant. It comes from a tree believed

indigenous to China, while cinnamon is a native plant of Sri Lanka and southern

India. In sources too many to mention,

I have discovered cinnamon referenced as an ingredient. Achaya noted that they appeared to be

interchangeable in pre-Moghul and Moghul cuisine.

Cloves: Achaya

mentions the oldest clove found burnt to a floor in an archaeological dig. It dates back to approximately 1721 B.C. (give or take a millennium!). Originally from the Spice Islands, they were

known to have been cultivated as far west as Rome a hundred years before the

birth of Christ. They and their

essential oils have been used in Ayurvedic medicine for centuries as a

painkiller. In modern curry powders from

my own research, they appear to be interchangeable with allspice. Clove or clove oil may have been added to

food by Indian cooks.

Coriander seed: Yes,

it’s from the same plant as cilantro.

But the two spices are so far apart, there’s good reason to call them

separate names. The seed is actually the

dried fruit of the plant. Achaya notes

that coriander was often used as a thickener.

It is a key ingredient in both garam masala (a traditional blend of

whole spices common in Indian kitchens today) and “traditional” curry

powder. It’s native to the southwestern

part of India through the Middle East and northern Africa. From my research, coriander is apparently

used much as file powder (the ground leaves of the sassafras tree) are used

here in North America as a thickener. I

might extrapolate that coriander and its cooking could be the bridge between

the term “curry” and its synonymous usage for the English term “gravy” in

modern India.

Cumin: Also

a spice used since antiquity, cumin is native to most of India. It’s the dried seed of the parsley relative Cuminum

cyminum, and has been used in both Eastern and Western cooking extensively. To me, the scent of cumin reminds me of the

scent of chili (the dish, not the spice).

Achaya noted a prevalence of cumin throughout his archaeological

travels.

Fenugreek leaves: These

are commonly known today as Methi leaves.

Both the leaves and the seeds of the fenugreek plant have been found at

archeological digs and dated back as far as 4000 BC. The leaves are used not only in Indian food

as a spice for the curry gravy but also in yogurt and as a hair

conditioner. The leaves, to me, smell

like what you encounter when you enter a modern Indian restaurant.

Fenugreek seeds: Have

you ever been told you smell like curry (guilty!) -- if so, chances are, you’ve

been eating fenugreek seeds in some form or fashion. The oils from the seed of the fenugreek plant

give the aromas of Indian food (and consequently, people who eat it) that

certain “tang” we all recognize.

Garlic: Where did it

come from? Everywhere! There are varieties of garlic found in almost

every region of the world not covered with ice.

But whether garlic was used in period Indian dishes as an addition to

curry-type dishes is up for debate.

Achaya did document it in a few of his digs, but overall it’s not a

spice that’s encountered in the typical pre-British influence kitchen.

Ginger: Strangely

enough, this most Indian of spice is also questioned as an ingredient in period

Indian dishes. There is documentation of

candies in South India prepared with ginger, but not much to substantiate that

it would have been used in other parts of the subcontinent before Akbar. I would personally postulate that its arrival

came with exploration, both from European influences and through the expansion

of the Moghul Empire from the late 15th Century onwards. However, I did find it included in many of

the modern curry spice blends I encountered.

Mustard seed: The

seed is often used to flavor dishes but not often eaten whole. It’s often cooked in oil to take advantage of

its essential oils, which produce a distinctive tartness to a dish. The Indian mustard seed is light brownish in

color; other varieties range from a light yellow all the way to black. Achaya’s work notes a wide spread across the

Indian subcontinent of mustard varietals.

In curries it carries a bit of a zing.

Pepper: Black,

white, red, and green peppercorns all come from the same plant, piper

nigrum. It is not related to the

capsicum peppers of the New World. Long

pepper or pippali (piper longum) is from the same genus and retains much

of the “heat” we consider pepper to bring to our dishes. Yet its flavor is considered to be more

pungent. Pippali is still a common

ingredient in India with dishes, but there and especially in British and

American-influenced applications the long pepper has been replaced with spices

from members of the capsicum family, which would not have been utilized in

India until the early 16th Century.

Peppercorns are another of the spices that Achaya found common with most

pre-British influence kitchen ruins.

Star anise: This

spice is sometimes confused with anise, but the two are completely

separate. Star anise are star shaped

fruits harvested just before they ripen.

They originate in China and are a key component of Chinese Five Spice

Powder. First records of it being brought

to Europe in the late 16th Century.

It is cited as a component of many period Indian applications.

Turmeric: This

root (or rhizome) is what gives much of Indian food its yellowish

coloring. It’s also used in cosmetic

applications to give a glow to the skin of the wearer -- and as a hair growth

deterrent. The flavor is mild but often

used as a base for other flavors to build on.

On the use of capsicum

peppers: red peppers, chillies, and other “hot” peppers come

from the New World. There are some who

will tell you over and over and over again that these spices were not used in

period. They are almost but not quite

right. Capsicum peppers did not come to

the Old World until the “discovery” of America. However, while they were used

mostly for medicinal purposes in the West, they were embraced by many Eastern

cultures. There is some debate over

whether the introduction of capsicum lead to the end of cultivation (and

therefore near extinction) of what is considered in India to be the “long

pepper,” the spice pippali. I have found

it difficult to locate pippali in the States.

Once I had researched the

different spices and created my blend, I shared that blend with others. The original blend itself, from spices I

ground in the coffeemaker:

A tej pat leaf (I used bay

leaf in a pinch)

A tablespoon cardamom powder

A tablespoon of cinnamon

powder

A half teaspoon of ground

cloves

A tablespoon of coriander

powder

Four tablespoons of ground

cumin

A pinch of methi leaves

A teaspoon ground fenugreek

½ teaspoon mustard seeds,

ground in my coffee grinder (ground mustard doesn’t work)

½ teaspoon ground black

pepper

2 tablespoons powdered

turmeric

I chose not to use ginger or

garlic partly because it seemed that the spices weren’t used all through India,

but moreso because I didn’t like what they brought to the table when mixed with

the other ingredients in my curry powder attempt. The taste, to me, was too sharp and a bit too

modern.

This mix got me through my

first attempt at Indian cooking in a feast, but I wasn’t satisfied with

it. I did more research, and read

through the works of Collingham and Achaya, and also Joyce Westrip’s book Moghul

Cooking: India’s Courtly Cuisine. After this and after discussions with cooks

at Little Rock restaurants Star of India and Kebab and Curry in 2005, I started

experimenting with a spice mixture that comes closer to what a cook would have

used in the 16th Century. I

learned about the necessity of heating spices in ghee and letting them release

their essential oils. I also determined

that the whole idea of curry powder is prevalent today even with these cooks,

simply on the basis of consistency and ease.

But there are still cooks who want to retain the traditions of whole

spice curried dishes. With this

knowledge and assistance, I came up with my own, better spice blend. Unlike the other blend, I keep the whole

spices available to use when I make curry at home. The amounts sometimes vary depending on what

I’m cooking or what mood I’m in, but the base curry has come to this.

Four green and one black

cardamom pod

1 2-inch section of cassia bark or 1 one inch section of cinnamon bark or 1

tablespoon chopped cinnamon bark (do not use ground)

1 clove

2 teaspoons coriander seeds

1 ½ Tablespoons cumin seeds

1 teaspoon fenugreek seeds

1/2 teaspoon mustard seeds

1/2 teaspoon peppercorns, freshly and coarsely ground

1 star anise

1 bay leaf

1 ¼ Tablespoons powdered turmeric

1 healthy pinch methi

(fenugreek) leaves (appox. 1 tablespoon)

As you can see from this listing,

I am still not confident with cooking with some whole spices, in this case the

turmeric. Experimentations with this

root have come out with a flavor that’s far from comfortable with my

Americanized tongue, and my one attempt at using the whole root in a group

situation failed to enthrall the diners that partook of my dibblings. Besides, the root is somewhat wet, which

makes putting it into the grinder or pulping it in the pestle come out as a

paste that has to be refrigerated if not used right away. It’s far more convenient to me to have the

dried variety of the building blocks of

my own curry powder available for me to just throw into a skillet with

whatever I decide to cook up.

When it does come to advance

preparation, especially as it happens in SCA practice (ie, feast cooking for

events), I have found it far easier to rely on a pre-made powder of my own

creation. Finding the time to listen for

popping seeds or getting spices to evenly roast when the curry is just one of a

couple of dozen dishes heading for the platters and plates of feast diners,

having a powdered contingent on-hand that allows me to sidestep the roasting

and mortaring process has been a blessing.

I can simply start at the roux stage and go from there.

Now, I did learn a bit

more. From attempting the making of

curries with the whole spices, I’ve learned to start out with a dry skillet and

place spices that come from seeds in it.

Let it toast a bit. Cumin and

mustard seeds will pop… and there’s a distinctive roasted scent similar to meat

cooking that emanates. When they’re

toasted, take them out and let them cool a little, then grind them. While that’s going on, throw the rest of the

ingredients except the methi leaves and the turmeric powder into the same

skillet with a tablespoon of ghee (that’s clarified, shelf stable butter). Keep them from burning but get them

thoroughly heated and mixed. Add the

ground seeds back in along with the ground turmeric and stir it like a

roux.

Now comes the fun part. While I was doing all that research on curry

powders and the like, I discovered something.

There’s always a liquid component in meat dishes. Sometimes it’s yogurt, buttermilk, or

milk. It can also be fruit juice,

coconut milk, or honey. The general rule

is to treat that spice blend like a gravy -- keep it moving like a roux so it

won‘t burn (and if it does burn, throw it out).

Thin it with the liquid component and then add in the meat or vegetable

that will cook in it.

Strangely enough, most of

what we get as far as entrée dishes at Indian restaurants today seem to be

based on this basic equation (except, of course, that the gravy starts with the

powder). For instance, add ground

cashews and cream to the gravy equation and you have a Korma sauce. Tomatoes and potatoes with some capsicum-type

pepper element brings you to a Vindaloo.

Masala is the same sort of spice gravy but with a tomato component --

which is sometimes ketchup.

Even non-sauce dishes come

from this gravy. Biriyanis in period

were the spice gravy layered between layers of rice and either meat or

vegetables in a heated pot that was then left to cook on its own in the embers

until ready to serve (think medieval casseroles). Today it’s meat soaked in the curry gravy

that’s then mixed by hand into rice and allowed to sit for a little bit.

But I digress.

The past several years of

accumulating this information and practicing its applications on my friends and

upon willing feast goers has brought me to the conclusion that, while there is

no such thing as a period curry powder, most of the same spices were used in

Indian cooking. I have learned that

though I have created a pretty decent recipe that others could follow to create

a simulation of my curried dishes, that on any given day I might choose to throw

in this or that or change the amounts of spice used or even to omit something

that I usually utilize. By doing so, I

have started to cook a little closer to my culinary predecessors.

However, as a feast cook,

time and ease will likely leave me clinging to my homemade curry powder. I am not comfortable with the results of

freezing or otherwise utilizing advance preparation methods in my curried

dishes. The results, to me, don’t taste

as fresh. Therefore I find myself

offering this compromise when cooking for crowds of 100 or more. It is my modern compromise to historical

cookery that seems to be acceptable to the palates for which I cook.

Bibliography

Achaya, K.T. Indian Food: A Historical Companion. Oxford University Press 1994.

Apicius. De Re

Coquinaria (The Roman Cookery Book). Translated by Barbara Flower and

Elizabeth Alföldi-Rosenbaum. London and Toronto: Harrap, 1958.

Bernier, Francis. Travels in the Mughal Empire. Original publication in France in

1670. South Asia Books 1989.

Collingham, Lindsey. Curry, A Tale of Cooks and

Conquerors. Oxford University Press

2007.

Various Authors. The Bible. King James Version.

Westrip, Joyce. Moghul Cooking: India’s Courtly Cuisine. Serif Publishing 2005.

A note on the display:

While an attempt was made at

a period-esque display, this wasn’t completely possible. Requirements being what they are (for each

entry to be presented at serving temperature and for entries to be available

from 9am to after court), I had to improvise.

Therefore, the applications of curried chicken are within the electrical

device. However, the curry powder

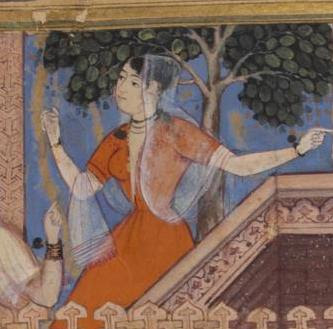

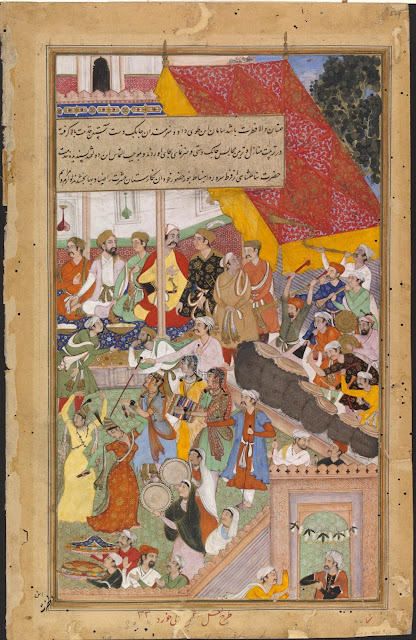

display itself is presented on a dish I painted myself. The design is based on the small five petaled

flowers seen in the borders of several examples of Mughal paintings of the 16th

and 17th Centuries. The

specific examples that inspired the painting of these items comes from the

British Library’s exhibition of an illumination, King Khusraw hunting, by Abd

us-Samad dated 1595.

The Period-Style Curry

Four green and one black

cardamom pod

1 2-inch section of cassia bark or 1 one inch section of cinnamon bark or 1

tablespoon chopped cinnamon bark (do not use ground)

1 clove

2 teaspoons coriander seeds

1 ½ Tablespoons cumin seeds

1 teaspoon fenugreek seeds

1/2 teaspoon mustard seeds

1/2 teaspoon peppercorns, freshly and coarsely ground

1 star anise

1 bay leaf

1 ¼ Tablespoons powdered turmeric

1 healthy pinch methi

(fenugreek) leaves (appox. 1 tablespoon)

2 Tablespoons honey

4 Tablespoons ghee

1 pound chicken breast

Place pan over low to medium

heat. Spread cumin, cardamoms, cassia or

cinnamon, clove, coriander, fenugreek and mustard seeds, star anise and bay

leaf over the bottom of the pan. Grind

peppercorns and add to pan. Listen to

the pan and stir frequently until the cumin and mustard seeds begin to pop

(they sound a little like Rice Krispies).

Remove pan from heat and let cool a moment.

Remove star anise and bay

leaf. Add other ingredients to a mortar

or a purposed electric grinder. Grind to

a coarse consistency (think coffee grinds).

In the same pan, heat ghee

over low to medium heat until melted.

Add ground mixture and turmeric to the pan (it works better this way;

otherwise, the powder will clump, as I discovered in my tests). Stir together until it becomes gravy-like, a

roux of spices. Add the honey and stir

to combine. Add the bay leaf and the

star anise back in. Add in the methi

leaves and stir.

Slice the chicken breast into

½ inch slices and place in pan, turning to coat in the spice mixture. Cover and let simmer on medium heat for five

minutes. Remove lid and stir. Add up to ¼ cup water if the spices are too

clumpy. Cook uncovered until the chicken

is almost cooked through (155 degrees F).

Remove from heat and let sit 10 minutes (the chicken will come to 165

degrees F). Remove bay leaf and star

anise. Serve curry on its own, over

rice, or with naan.

The Powder-Based Curry

1 teaspoon ground bay leaf

1 Tablespoon cardamom powder

1 Tablespoon cinnamon powder

½ teaspoon ground cloves

1 Tablespoon coriander powder

4 Tablespoons ground cumin

1 teaspoon methi leaves

1 teaspoon ground fenugreek

½ teaspoon mustard seeds,

ground in a purposed electric grinder

½ teaspoon ground black

pepper

2 Tablespoons powdered turmeric

4 Tablespoons ghee

2 Tablespoons honey

1 pound chicken breast

Place pan over medium

heat. Melt ghee. Add spice blend to ghee and stir into a

roux. Add honey and combine.

Slice chicken breast into ½

inch slices. Add to pan and coat with

ghee-spice-honey mixture. Cover and let

simmer on medium heat for five minutes.

Remove lid and stir. Cook

uncovered until the chicken is almost cooked through (155 degrees F). Remove from heat and let sit 10 minutes (the

chicken will come to 165 degrees F).

Serve curry on its own, over rice, or with naan.